|

|||||||

|

Jim Smith I was the third member of the Vought (LTV) STRAAD Team. I left for Cubi Point just after Christmas of 1966 and arrived in early January after a week or so in Atsugi, Japan. I traveled in the company of Cmd. Chuck Reid who was replacing Cmd. Holton as STRAAD Officer. Also traveling with us was Don Tolbert, a MacDonald engineer. On the first day at Cubi Cmd. Holton showed us around a carrier in dock to familiarize us with the ship. Then he advised me that the next morning I would be on my way to the USS Ticonderoga to assess an F-8 that had experienced a fire in the aft section.

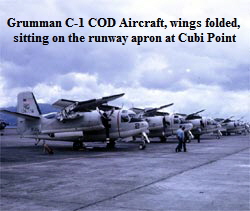

The seats in the aft were isolated from the crew. These airplanes were referred to as COD’s for Carrier On-deck Deliver and were operated by VRC-50. Normally two COD flights per day were made to each of the carriers. In 1967 there were normally three or four carriers on station at any one time. The C-1 was an old airplane with few high tech features. There was no onboard radar so navigation was by dead reckoning once TACAN range of about 100 miles was exceeded. The flight would be a direct line to Da Nang. Once the Da nang TACAN was contacted the crew would check fuel consumption and track to determine if sufficient fuel remained to go direct to the carrier. If not, a stop would be made at Da Nang. Once fuel was verified the flight would turn north around Hanian Island to the carrier track near Hifong harbor. The no-wind time for a C-1 from Cubi to Da Nang was about 4 hours. The range of the airplane was about 6 hours. Fuel was always a concern on the flights and VRC-50 operated with fuel reserves of minutes. There were a couple of surprises for me on this first flight. I had been advised that on the larger carriers that the C-1’s would deck launch (take off the angle deck without catapulting) but the Tico was a small WWII carrier that an angle deck had been added. For my return flight from the carrier we boarded the C-1 at the aft end of the deck. The pilot ran up engines and I thought we would taxi to the catapult. Instead, he went to full power and off we went. As we left the angle deck the main landing gear extended rapidly, indicating that we were just barely to flight speed. I thought that was great not having to catapult. That is until I talked with the pilot. As it turned out I was temporarily rooming with the pilot of this particular COD. He later told me that a C-1 accelerates to 40 knots in the length of the angle deck and that stall speed for the C-1 is 70 knots. The ship is moving at around 20 knots. In a no-wind takeoff the plane sinks until flight speed is obtained. After that a cat shot didn’t seem so bad. The second event on that flight had to do with head winds. We departed the ship just before dark. The departure was delayed because of concern for the inbound COD which was overdue. It finally arrived after a fuel stop at Da Nang. Since the inbound COD had headwinds our crew said we should make it in about 4 hours or less. What they didn’t tell me was that often the winds change when it gets dark. Again I was isolated behind a cargo crib and this time I was the only passenger. Four hours came and went and we were still cruising. Then five hours passed, then six hours; we are still at altitude. My only thought was that the range was six hours, or so I had been told. I was mulling over what it might be like to ditch in a C-1 and at night at that. At six hours and 5 minutes (I am watching the time closely) I can see the lights of Cubi. We began our decent at about six hours and ten minutes. I rode to the BOQ with my Pilot/Roommate. I guess he figured I was concerned because he said we still had some fumes left. Because of the limited range of the C-1 the crew would not operate the heaters. We flew at either 9000 ft or 10000 ft depending on direction. It was very cold in the cabin and a strong draft of cold air circulated at floor level. To keep feet warmer I would sit with my feet up on the fuselage frame.

The smaller carriers were equipped with F-8 Crusaders, A-4 Skyhawks and A-6 Intruders as well A-3 Tankers. The larger carriers were equipped with F-4 Phantoms, A-4’s and A-6’s as well as support aircraft such as RA-5’s. I found the visits to the carriers to be very exciting and fascinating. It was intriguing to watch flight operations especially under wartime conditions. The catwalk around the tower at the Pri Fly (Primary Flight Control – equivalent to a Control Tower) level was the normal place to watch air operations. It was referred to as “Vultures Row”. Although each visit had its moments, there are several occasions that remain fixed in my memory. During one visit to the Ticonderoga I was watching landing operations after a mission. An A-4 was approaching. He missed the wire and immediately I thought something is not right. At that point the A-4 went off the bow of the angle deck and continued to descend. I then realized what had seemed wrong; he was rolling on the deck rather than bouncing back into the air as a normal “Bolter”. Within seconds the plane struck the water just as the ejection seat fired. Immediately the ship turned bow toward the descending pilot to keep the screws away from him. The helo was over him with a paramedic in the water within seconds of the pilot hitting the water. He was on the deck and in a stretcher within five minutes of when the seat fired. He was okay. It was an impressive performance by the ships personnel. That night we were able to watch the Plat camera views of the landing. The Plat cameras are in the deck and record all landings. I was told by squadron personnel that the pilot had reported that he could only get 80% power. Those in the know told me that that is not enough power to bolter (go around) in an A-4. So they knew if he missed the wire he would go in. Questions were raised as to why the barricade was not raised. According to the squadron the Air Boss thought that erecting the barricade would take too long thus jeopardizing other planes that were low on fuel. The barricade is a strong net that can be raised across the deck to capture an airplane that is in trouble and misses the wire. The captain said an inquiry team was coming aboard to investigate the issue. Another notable event occurred aboard the Kitty Hawk. It was my first visit to that class of carrier. I asked the Squadron CO where the best place to watch operations on the Kitty Hawk. He said, “Come on I’ll show you”. He took me into Pri Fly where air operations are controlled and directed. The squawk box was picking up chatter from the returning crews. I heard calls of “bandits”. Suddenly the tempo increased as the “air boss” received an emergency call from an unidentified aircraft that he was out of fuel and needed to land and asked for identity of the carrier. In rapid fire the air boss ask for him to identify and told him he was cleared to land on the Kitty Hawk and waved off other traffic in the pattern. After the pilot identified himself as F-8 Crusader no.----- from the Bon Homme Richard and that his fuel state was 600 lbs, he proceeded to inform all that he had shot down a Mig. He was flying an old F-8c. The F-8c’s were deployed to replace F-8E’s that were being rotated to Vought for modernization. He already had two Mig kills. The two F-4 squadrons on the Kitty Hawk had two kills between them. The ready room slogan of F-8 squadrons was “If you are out of F-8’s you are out of fighters”. The ship planned to refuel the F-8 and send it on to the Bon Homme Richard but it was discovered that it had received a 27 mm round up through the air intake. I was called to assess the damage. I told them that it was quite likely that there was FOD to the engine. At first the Bonny Dick wanted to send a crew over with an engine for replacement but since the Kitty Hawk was heading for Cubi the next day it was decided to leave it on board and off load at Cubi. That night the ship’s crew painted graffiti on the F-8. The next morning the entire crew was called on the carpet by the Captain. By the time we got to Cubi the F-8 was clean. I was invited to ride the ship into port but the STRAAD Office said for me to come on the next COD. By the time the COD launched we were close enough to Cubi that the pilot turned the heat on. Also we detoured through Manila to let someone off. The pilot gave us a low level tour of Corregidor. One thing that the Vietnam experience made apparent was that the hydraulic systems on modern aircraft were vulnerable to small arms fire. The Bon Homme Richard experienced three occurrences of damage to the F-8 utility hydraulic system. The squadron procedure was to drop the landing gear first. This would dump the hydraulic fluid through the leak preventing the raising of the wing (The F-8 wing was two-position that is raised to increase angle of attack of the wing for landing. Also the landing flaps deploy automatically when the wing is raised.). Also due to the utility system being out they could not deploy the IFR (in-flight refueling) probe. With the wing down and no flaps the landing speed is about 180 kts rather than 130 kts. This makes for a very hot landing. One of them slammed into the round down (the aft edge of the deck) and got airborne again. The pilot ejected. Another bingoed to Da Nang (where there is a 10,000 foot runway). The third one landed successfully but sustained damage. I was called out to assess the damage. I suggested that the procedure be changed to raise the wing first and then the gear. The gear can be lowered using g-forces if necessary. This is the procedure used by some F-8 operators. I don’t know if they changed the procedures or not. While on the Bon Homme Richards I met Lt. Kennedy who was the maintenance officer for the ship. He was an unusual man. He had come up thru the ranks and was a very good maintenance Officer. He believed he and his crew could repair anything and was very jealous of this capability. He wanted minimum help from STRAAD. He and I got along well. He was also a pilot (private license) and was checked out in a C-1. He talked the ship’s Captain into letting him make five carrier approaches and landings in the ship’s COD to qualify as a carrier rated pilot. He claimed to be the only non-navy pilot qualified for arrested landing in a C-1. On my third trip to the Ticonderoga the COD had already turned north around Hanian Island and was only about 30 miles from the ship when the crew was advised that an Alpha Strike was underway and we could not land (unless we declared an emergency). An Alpha Strike was when conditions were exceptionally good over the target and all ships would launch every available aircraft. We turned back to Da Nang and as we turned off the runway one engine quit. Because the C-1’s were operated so close to their range, it was customary to placard each fuel gauge with the amount of fuel remaining when that engine would exhaust. On this occasion the pilot said we should have had five more minutes of fuel. That didn’t make me feel any better. This particular crew was not very friendly to a civilian (that was the exception). They told me to be at the airplane at 2:00 pm for departure and they left to get the plane refueled, etc. They pointed to where the officers club was. I had not had any thing to eat so I went looking for something. I didn’t find the club and returned to the plane. They were back at the plane getting ready to depart. It was well before 2:00. I guess I would have been left had I not returned. The next day I checked on the return flight and was told it would be in the afternoon. So I was down in the ready room killing time when I heard my name over the intercom with the direction to report to the flight deck. Expecting a message from the office I went up the several levels to the small room in the tower at deck level that served as the check in for COD flights. A launch was getting under way. I was told the COD was loading and I should board. I told them that I didn’t have my bag because I was not expecting to depart this soon. The ATCO (I don’t remember what that stands for but he books the flights) called the Air Boss and he held the launch while a seaman went for my bag. I think that was an indication of the importance the ships placed in the STRAAD office. When my bag arrived I was rushed to the COD sitting on the catapult. As I strapped in the engines began to increase power for launch. I was handed a Mae West but I wasn’t about to unstrap to put it on. At that second we launched. The C-1 launches at about 3.4 to 4 g’s. Since the seats face aft, you are pushed hard into the straps. Severe injury can occurred if the straps fail or aren’t properly buckled. On return from a trip Cmd. Holton said I needed to go to Thailand. An A-4 from the Bon Homme Richard had bingoed to Udorn Thailand after being hit over target. The Air Force had a large base at Udorn. Larry Dingus, the Douglas engineer, had been sent up there to access the situation and message the office as to whether the ship’s crew could make the repairs. This was one of Lt Kennedy’s planes and Larry was not aware of the Lt’s desire to do most of his own repairs. So Larry sent a message to STRAAD office with copy to the ship with his assessment of the damage and that his opinion was that it was beyond squadron capability to repair even for a ferry flight. Then Larry disappeared or seemed to as several days had passed with no word. The ship and particularly Lt Kennedy were upset over the message and were determined to send a crew to repair the airplane. Cmd. Holton was just as adamant that STRAAD would do the repairs. Cmd. Holton sent two mechanics and me on our way to Thailand, and he went with us. We went by van to Clark AFB and took a C-130 to Udorn with a stop at another base in Thailand. We arrived and immediately went to the airplane. Lt. Kennedy and his crew were there. Cmd. Holton took a quick look at the airplane, told me he would let us know what to do and got back on the C-130 back to Clark. We cooled our heels for a day or two until it was decided that we would work together to repair the airplane for flight. Once started the repairs didn’t take long. Since we traveled on Navy orders we were entitled to stay in military housing. However, there was none at Udorn so we had to stay in town at the only hotel. I had brought very little money with me and was concerned about the expenses. We were told not to drink the water so we lived on cokes. The Seventh Fleet Liaison Officer had a house in town and invited us to dinner one night. I wasn’t sure why there was a Navy officer at an Air Base in northern Thailand. Once the plane was repaired we prepared to return the way we came. To our surprise we found that we could only get a flight from Udorn to Bangkok. At Bangkok we would have to get a MAC flight to Clark. The in-country flight arrived at the International Terminal in Bangkok. The MAC flights used a terminal on the opposite side of the airport. Since we normally traveled from one military base to another on military aircraft we usually didn’t clear customs. That was the case here. I didn’t expect to have to go to the International Terminal. I was concerned that we might be required to clear customs there. However, we weren’t required to. We went to the other side to the MAC terminal and were told by the ATCO that it would be three or four days for a flight. This was an Air Force ATCO and was not familiar with Navy orders. He insisted that I had to have a civil service number. The two men with me had the numbers since they were civil service employees. I tried to explain that I was a consultant to the Navy and did not have such number. After several minutes of debate I finally gave him my social security number and he was happy. Then he said he had to have the original of our order. We finally convinced him that we had to keep the original. He said check in at 8:00 am the next morning. The Bangkok airport is about fifteen miles from the city. We took a taxi in to the military billet office to get lodging. We were told that they had billets for enlisted personnel only and that officers obtained their own lodging. Since I was nearly out of money I insisted that my orders said I would be provided lodging. So they put us in an NCO hotel in town. The next morning we took a taxi to the terminal to see when we might get a flight. The ATCO said there was a C-141 leaving later that morning that we could get on. We told him we had left out bags at the hotel. He said that if we could go get the bags and be back by 9:00 we could make the flight. We grabbed a taxi and told him to hurry but don’t kill us. He could do well on the racing circuit. We made it to the hotel in about 20 minutes, checked out and our driver made another mad dash to the airport. We arrived right at 9:00 only to be advised that the flight was delayed until 11:00 that night. We stashed our bags and decided to sight-see. As we left the terminal our taxi driver was waiting to see if we would need to go back to town. We told him we wanted to see the town and ask how much he would charge to show us around. He said he would show us around and at the end we could pay him what we thought it was worth. I had wanted to get some uncut jade so he took us to a factory outlet that had all types of gems as well as other gifts, etc. I bought some jade and an ivory elephant, about all my budget would allow. We told our driver we would go to a movie. We saw Blue Max. When we came out our driver was waiting. He took us to the airport about 6:00. We gave him ten dollars American, which he was very happy about. Not surprisingly the flight had been delayed again, this time to 1:00 am. Shortly before departure we were summoned by the ATCO, a different one, who again wanted to argue about our orders and my lack of civil service number. We finally departed and over-flew Cambodia to Clark AFB. The C-141 was fully loaded with cargo and only had jump seats for about ten passengers. On my return from Thailand I learned that the A-4 repair incident had precipitated a “situation” at STRAAD. The result was that Cmd. Reid was insisting that Cmd. Holton give up command and move on. Cmd. Reid was in charge and Cmd. Holton was writing a report covering his tenure. One thing Cmd. Reid had accomplished while waiting to assume command was to arrange for the engineers to obtain multi-entry visas so we could come and go legally. Prior to my trip to Thailand Cmd. Holton had told me he wanted me to go to Da Nang, not for any particular reason but to just have a presence there. He had arranged for a billet with the marines in their NCO area. I reluctantly agreed but really didn’t like the idea since there were no airplanes to assess or repair. I went to the terminal to depart. The ATCO ask to see my passport and he stamped it as leaving the country. I told him to void the stamp and remove me from the flight. I was not about to go to Da Nang without entry back into the Philippines. I would have had to hitch a flight to Saigon and find the Philippine Embassy to obtain another visa. I called Cmd. Holton and told him I was not going until we could get multi-entry visas. When I returned from, I believe, the Kitty Hawk trip he asked if I was ready to go to Da Nang. I asked if he had arranged for the visas. He became upset and allowed as how he thought the whole thing with visas was so we could have a vacation every 3 months. After he cooled off he asked Cmd. Reid to pursue getting the visas for us. I went to Manila for two days and got the visa. We received a message from the USS Hancock that they needed an engineer and specified an LTV representative. Cmd. Reid told me about the message but said that the Hancock was now steaming toward Japan and was out of COD range. He asked if I would like to go to Japan. He said I could take a day or two in Tokyo on the way back. WestPac operated a C-54 that flew between Japan, the Philippines and Okinawa carrying crews where they needed to be. It was passing through Cubi on the way to Japan. Cmd. Reid got me on the flight. I left about 6:00 in the evening. The other passengers were VRC-50 crews rotating to Japan. We arrived at Atsugi about 3:00 in the morning. I had to wake up the duty officer to get my passport stamped. I slept a few hours then went to the terminal to arrange transportation to Sasebo where the Hancock was docked. I was booked on Air America (really) to a base about 4 hrs drive from Sasebo. I can’t recall the name of the base. From there I went by bus to Sasebo arriving on Sunday. Most of the ship’s crew was on pass but an officer on duty had been briefed to show me the airplane. It was an A-4. This was Monday, April 17, 1967. After I completed the damage report on the A-4 they asked if I would also look at an F-8 that was damaged. The F-8 had been jacked with a MLG bulkhead tie down in place. A section of the bulkhead was pulled out. There had been several attempts to repair damage to this heavy machined bulkhead in the past without success. I had reviewed these efforts as well as Japan Aircraft’s technique for replacing the bulkhead. I told the squadron I would go to Japan Aircraft at Atsugi and review the F-8 Stress Analysis Report (which I knew was available there) before making a decision. The Navy had Japan Aircraft under contract to repair and modify navy aircraft. I was fairly certain that a bulkhead replacement would be required. They indicated that surface shipment by barge was available if I decided the aircraft needed to go to Atsugi. I had planned to visit Nagasaki while there but when I checked on travel I was told that I had to leave the next day or it would be several days before another flight would be available. I decided I couldn’t wait. When I arrived back at Atsugi I met with Mr. Takahashi, the Chief Engineer of Japan Aircraft. I had met him previously when we passed through going to Cubi Point and had corresponded with him over the years concerning F-8 repairs. He lent me the Stress Reports and I reassured myself that the bulkhead had to be replaced. He said he would arrange shipment of the aircraft to Atsugi. I decided against going in to Tokyo since it was raining and looked like it would be for days. I stayed the night at Atsugi NAS. At the officer’s mess I ran into Cmd. Holton. He was on his way home. He said he had signed my name to his report as the engineer. Although it was flattering I was not happy my name had been put on a report I hadn’t even seen. The next day I went to Yocotta AFB and got a flight to Clark AFB. At Clark I learned that the buses to Cubi Point were full. I then saw a Jack Rabbit (two seated pickup) arrive and leave off passengers. He was preparing to return to Cubi Point empty so I asked for a ride. He said to hop in. I was the only person in the car besides the driver. We caught up with the buses just before arriving at the gate to Cubi. The guards stopped the buses to check ID’s, even the officers. When the vehicle I was in pulled up the guard looked intently at the one individual in civilian’s clothes and gave me a smart salute and waved us through. He didn’t know who I was but wasn’t taking chances. Now that we had the proper visas I agreed to go to Da Nang to assess an F-8 of Marine squadron VMF232. This was the last few days of April, 1967. The aircraft had received a round up through the wing striking the rear spar of the center wing section. It was not possible to see all the damage without major disassembly. The squadron had X-ray capability so they X-rayed the wing. From that I could assess the extent of damage. I authorized a ferry flight to Japan for wing replacement. Shortly after I finished the damage report I was standing outside the hanger talking with squadron personnel when three F-8’s roared over us at very low level and at near sonic speed. Once over the hanger they zoomed up into a loop and circled for landing. I learned that VMF-232 and the neighboring squadron competed every month on the number of sorties flown. VMF-232 had won for the month. The fly by was to celebrate the win. This squadron had experienced two wings-folded takeoffs by F-8’s in a one-month period. One occurred because the normal procedure was to spread wings before taxi. On this one occurrence the pilot had folded the wings again to clear traffic on the taxiway and forgot to put then down. On take off he realized something was wrong and stayed in afterburner until he gained enough altitude and cleared the area so he could jettison his bombs. Just as he got rid of the bombs the afterburner blew out. He was able to return to base and land. The Hancock requested an engineer without being specific as to the need. Since STRAAD was trying to accommodate all requests I was sent out. On arriving at the ship I learned that an A-4 had made a nose gear up landing with a centerline fuel tank on. The fuel tank took most of the impact with damage being restricted to the nose cone. The damage to the cone was minor and consisted of failed hinges and some material damage. I told the squadron that the quickest solution was to replace the nose cone. The maintenance officer said he thought that was all that was required but had been told to call STRAAD. My next assignment was a call from the NAS Agana, Guam. They had an A-3 that got loose while being towed and collided with a hanger door. The radome was damaged but they could replace it. There was also damage to the radar bulkhead. I took a MAC flight (Braniff Airways) to Agana. I arrived on Sunday, Mar 19, 1967. When I checked in to the BOQ I found that President Lyndon Johnson was arriving that day to meet with the South Vietnamese Premier Nyugen Coo Ky. All available rooms in the BOQ were reserved and they offered me no help at all. I contacted the squadron CO and advised him that I needed a place to stay. He put me in a room of a officer on TDY. I was able to stand outside the BOQ and watch the President’s caravan. I would like to say that I saw him but I saw a black limousine with dark windows speed by. Air Force One was parked just outside the hanger where the airplane I had come to see was located. The key to repairing the A-3 was the replacement of an angle that ran vertically up the middle of the bulkhead. Two such angles provide support for the radar. The squadron had an angle that could be used but it was “0” condition. They said there was a heat treat oven there but the guy who knew how to use it would not be in until Monday. On Monday we found that the man in charge of the oven said that no one knew how to use it and there were no instructions. Someone suggested that the sub repair base across the island had heat treat capability. The angle was taken over there only to find that they had never heat-treated aluminum only steel. But they did find a manual on heat-treating aluminum and proceeded. I could only hope that the part had the proper strength. I was in Guam for a week. The next trip I had an opportunity to be aboard the USS Enterprise, at that time the only nuclear powered carrier. This was one of the two flights I made in a C-2. The flight only took three hours rather than 4 or 5. But since we had plenty of fuel we were told to hold in pattern for most of an hour before landing. The airplane had two wire antennas that were anchored to the forward fuselage and sloped back to each of the two vertical tails. As we orbited waiting for landing one of the wires came loose from the tail and began slapping the fuselage. The pilot trimmed the airplane differently and it stopped slapping. However, on landing approach it started again and banged all the way down. I was visualizing the wire sailing forward on arrestment right into the prop. We landed without incident. I don’t recall the airplane or incident that brought me to the Enterprise. The squadron received a message from the STRAAD office requesting that I be heloed to the Hancock as soon as possible. I was told that the Hancock was out of helo range but that the ship’s COD was leaving shortly for Saigon and would drop me off at the Hancock. When I arrived at the Hancock I learned that the reason it was out of helo range of the Enterprise was that it was reassigned south to support the invasion of the DMZ by the marines. We were only 15 miles offshore and that night I could see artillery fire. I returned to Da Nang for several days. The STRAAD CPO accompanied me as well as one of the other engineers. We traveled by pickup to Marble Mountain to assess damage to a UH-34 helicopter. Cmd. Reid wanted us to determine if STRAAD could put the helo back into service. After the assessment it was decided that we could not. I was told to go from Da Nang to Chu Lai to look at an A-4. When I arrived I was told the airplane was at the far end of the runway. The store ejection cartridge had burst, damaging the wing. The explosion forced sodium up into the fuel cell. As long as it was submerged in fuel it was okay. But if the sodium reached air it would burn rapidly. I climbed up on the wing with considerable reservations. I quickly found the damage to the rear spar and made a sketch of it. I told them I would design a repair that could be made at Cubi and we would send a team to repair it. As I was hanging around the terminal waiting for a flight to Da Nang a C-130 arrived. I learned that it was headed for Cubi Point. I signed on and sent a message to Cubi that I was returning directly from Chu Lai. James M. Smith

|

|||

|

Personal stories of their STRAAD tour experiences: Ed Grube |

|||

This first trip was similar to the others. I arrived at the terminal at 4:00 am for 6:00 am departure. In this case the plane was a Grumman C-1, a twin engine, high wing transport that would carry about eight passengers or less passengers and cargo. For this flight a cargo crib was installed in the middle of the cabin leaving a few seats aft and a couple forward for the plane captain and other crew. The seats face aft. The Navy considers this to be safer in the event of ditching at sea.

This first trip was similar to the others. I arrived at the terminal at 4:00 am for 6:00 am departure. In this case the plane was a Grumman C-1, a twin engine, high wing transport that would carry about eight passengers or less passengers and cargo. For this flight a cargo crib was installed in the middle of the cabin leaving a few seats aft and a couple forward for the plane captain and other crew. The seats face aft. The Navy considers this to be safer in the event of ditching at sea.

During my six-month tour the Grumman C-2’s were brought into service. They are Turboprop transports based on the E-2C’s. They are larger than the C-1 and hold about 16 passengers, or again, less with cargo. Compared to the C-1 the C-2 was high performance. It was fast, had good range, landed hard, and catapulted like an F-4. I only flew twice on C-2’s. Both times were out to the carriers. So I never catapulted in one. The C-1 had windows. So on landing you can see the ship and the wake and you can hear the change in prop pitch as the ship is approached.

During my six-month tour the Grumman C-2’s were brought into service. They are Turboprop transports based on the E-2C’s. They are larger than the C-1 and hold about 16 passengers, or again, less with cargo. Compared to the C-1 the C-2 was high performance. It was fast, had good range, landed hard, and catapulted like an F-4. I only flew twice on C-2’s. Both times were out to the carriers. So I never catapulted in one. The C-1 had windows. So on landing you can see the ship and the wake and you can hear the change in prop pitch as the ship is approached.  So you know when to anticipate touchdown and arrestment. The C-2 has no windows. Also, as a turboprop the sound is the same all the way down. So there is no way to know just when touchdown will occur. A light comes on that says, “Prepare for Arrested Landing” and the plane captain says something like “15 seconds to touchdown”. But you really don’t know for sure. You brace yourself and wait for a “BAM”. Until you feel the tug of the arresting cable you don’t know if you have landed or crashed.

So you know when to anticipate touchdown and arrestment. The C-2 has no windows. Also, as a turboprop the sound is the same all the way down. So there is no way to know just when touchdown will occur. A light comes on that says, “Prepare for Arrested Landing” and the plane captain says something like “15 seconds to touchdown”. But you really don’t know for sure. You brace yourself and wait for a “BAM”. Until you feel the tug of the arresting cable you don’t know if you have landed or crashed.